|

The Bank of Edwardsville

In December of 1816, the Illinois Territorial Legislature chartered the first territorial bank at Shawneetown. The development of territorial banks was a result of the economic conditions on the frontier. Gold and silver coins were in short supply. Additionally, the territory was flooded with paper money from hundreds of banks from numerous states, all of whom printed their own bills. Bank fraud was common and, with many denominations of bills being printed for hundreds of banks, counterfeiters were legion. The Illinois Territorial Legislature felt that the chartering of a territorial bankwould make it easier to spot counterfeit bills; furthermore, economic development of the frontier would be enhanced. Funds generated in the territory would be deposited in the territory and used to generate additional development. The Shawneetown bank was a significant success. As the only bank in the territory, it was in a very good competitive position. Further, it was founded at a time of economic prosperity, and its initial success allowed the bank to establish a strong foundation.

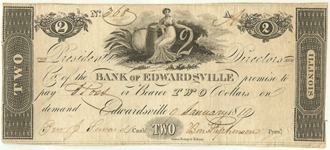

In January 1818, the legislature chartered three new banks. Of the three, only the Bank of Edwardsville opened. The bank began to selling stock in March 1818. Most of the stockholders were wealthy Kentuckians. Only $5,475 of the $30,000 stock held by Edwardsville residents was sold. In the fall of 1818, the stockholders elected directors including Stephenson, Ninian Edwards and a number of other leading citizens of the town. The board of directors elected Stephenson as president of the new bank. Not coincidentally, the last ad for Stephenson’s store appeared at this time. At the end of 1818, the bank was designated a depository for public money from the sale of lands in the Edwardsville District Land Office. The bank, therefore, opened with a significant advantage. It began printing paper money in early 1819. The only real restriction on the printing of money was that the amount of paper money printed was not to exceed the amount of gold and silver reserves held by the bank. In January 1818, the legislature chartered three new banks. Of the three, only the Bank of Edwardsville opened. The bank began to selling stock in March 1818. Most of the stockholders were wealthy Kentuckians. Only $5,475 of the $30,000 stock held by Edwardsville residents was sold. In the fall of 1818, the stockholders elected directors including Stephenson, Ninian Edwards and a number of other leading citizens of the town. The board of directors elected Stephenson as president of the new bank. Not coincidentally, the last ad for Stephenson’s store appeared at this time. At the end of 1818, the bank was designated a depository for public money from the sale of lands in the Edwardsville District Land Office. The bank, therefore, opened with a significant advantage. It began printing paper money in early 1819. The only real restriction on the printing of money was that the amount of paper money printed was not to exceed the amount of gold and silver reserves held by the bank.

Within months of the opening of the bank, a number of problems began to appear. The entire Northwest Territory fell into a significant recession. Land prices plummeted and the prices for products fell by nearly fifty percent. The bushel of wheat that had sold for $1.00 in 1818 now sold for fifty cents. The economic downturn coincided with the beginning of a number of vicious attacks on the bank by competitors from St. Louis. The St. Louis Enquirer ran articles in every issue attacking the organization and solvency of the Bank of Edwardsville. The attacks were self serving. Prior to the chartering of the Bank of Edwardsville, the proceeds from the land office sales were deposited in St. Louis in the Bank of Missouri. When the Bank of Edwardsville became a depository of land office money, The Bank of Missouri lost substantial business. The editor of the St. Louis Enquirer was Thomas Hart Benton, who later became an influential senator. Benton was, coincidentally, a director of the Bank of Missouri. Not content to attack the bank in Edwardsville only in the newspaper, the Bank of Missouri began to collect large amounts of Bank of Edwardsville paper money. Agents of the Missouri bank then presented these bills at the Bank of Edwardsville demanding specie (gold and silver coins) in return. The tactic was a blatant attempt to drive the bank out of business. The Bank at Shawneetown, which was not in competition with the Bank of Missouri and was so far away from St. Louis that the Missouri bank could not exchange its bills for specie, continued to prosper despite the recession. The Bank of Edwardsville struggled to survive.

Ironically, in August of 1821, the Bank of Missouri, the author of so many attacks on the Bank of Edwardsville, announced that it was “obliged to suspend its operations, with a view to the dissolution of the institution.” After trying for three years, the Bank of Missouri finally succeeded in destroying the Bank of Edwardsville by closing its own doors. The failure of the Bank of Missouri set off a panic and led to a run on the Bank of Edwardsville. Anyone holding paper money from the Bank of Edwardsville came to Edwardsville and demanded specie in exchange for their bills. The Edwardsville Spectator reported a scene worthy of the movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life.” “The news of the failure of the Missouri bank arrived at this place late on Tuesday evening, and on Wednesday morning the board of directors of the Edwardsville bank caused its doors to be opened at seven o’clock, and continued them open until several hours after the usual time of closing.” While the Bank of Edwardsville survived the original run, the harm had already been done. On September 3, 1821, the board of the Bank of Edwardsville announced in the Edwardsville Spectator that the bank had instituted a partial suspension of specie payments. Within a few months, the bank closed its doors.

|

|